In the Valley

2021

Installation. Concrete, metal, acrylic composite material, plastic, C-print, puzzle, and screen.

Exhibition view In the Valley.

2021.

Richter, Moscow

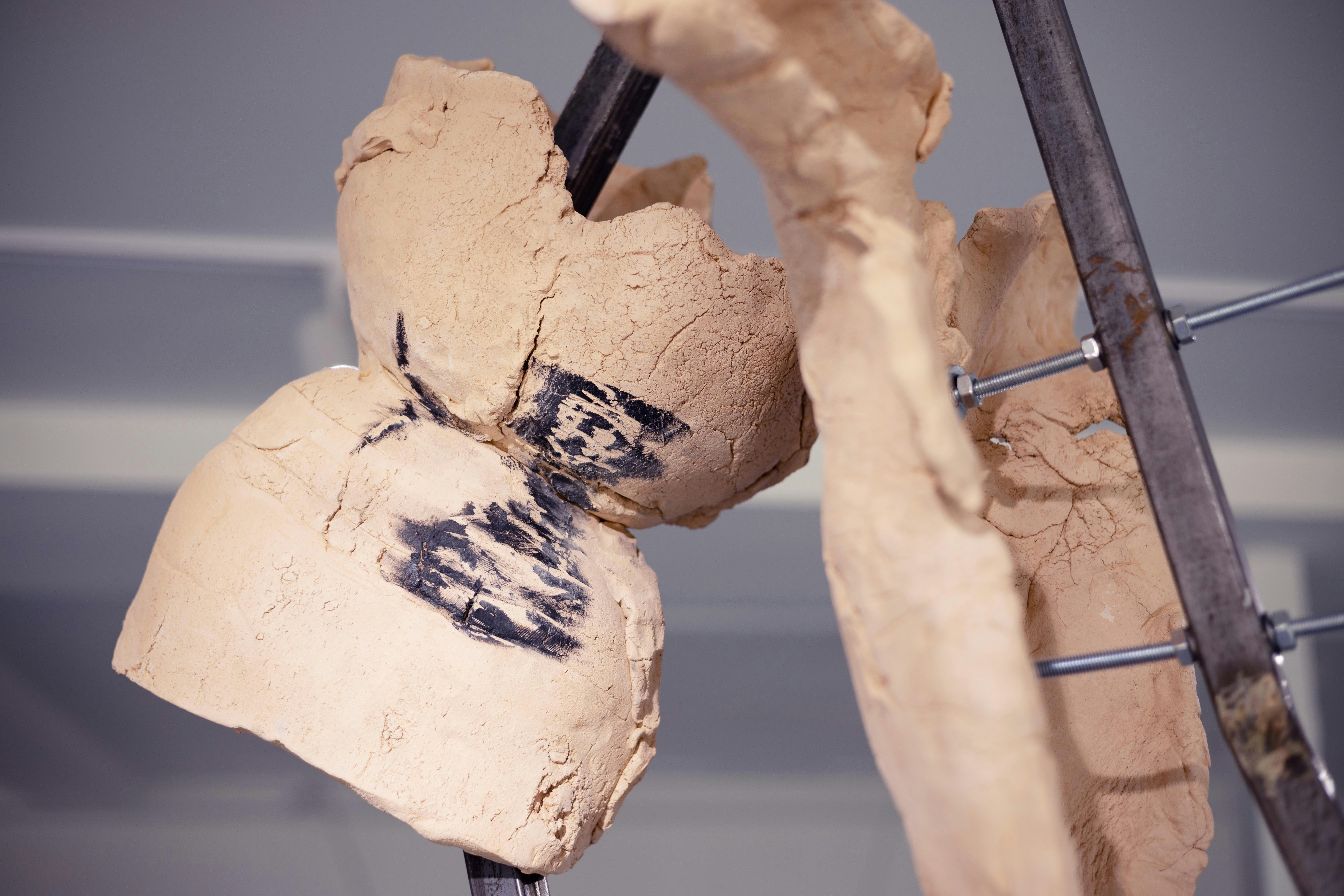

Object from the project In the Valley.

2021.

Architectural concrete.

60×27×20 сm (23,5×10,5×8 in)

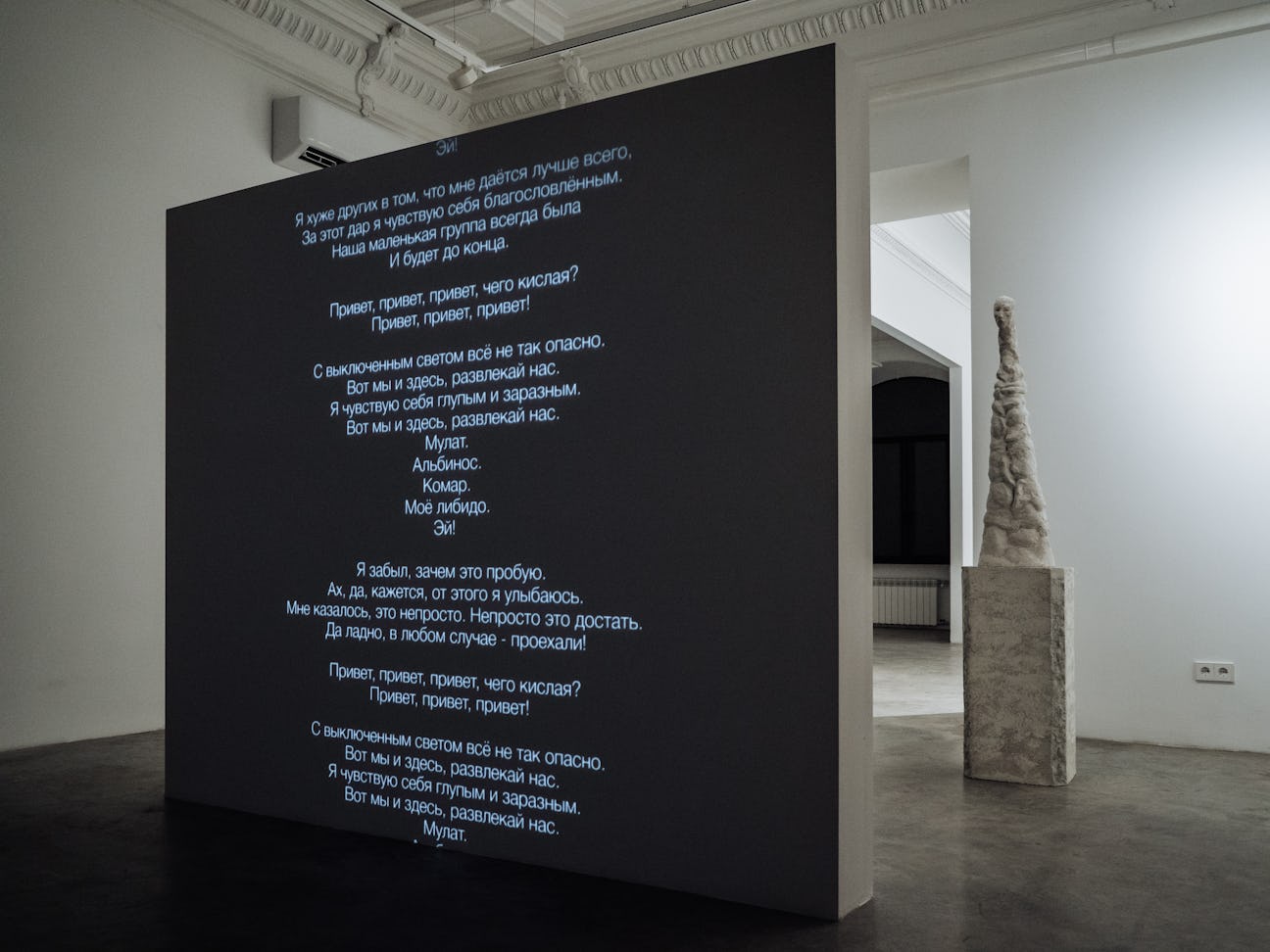

Exhibition view In the Valley.

2021.

Richter, Moscow

Exhibition view In the Valley.

2021.

Richter, Moscow

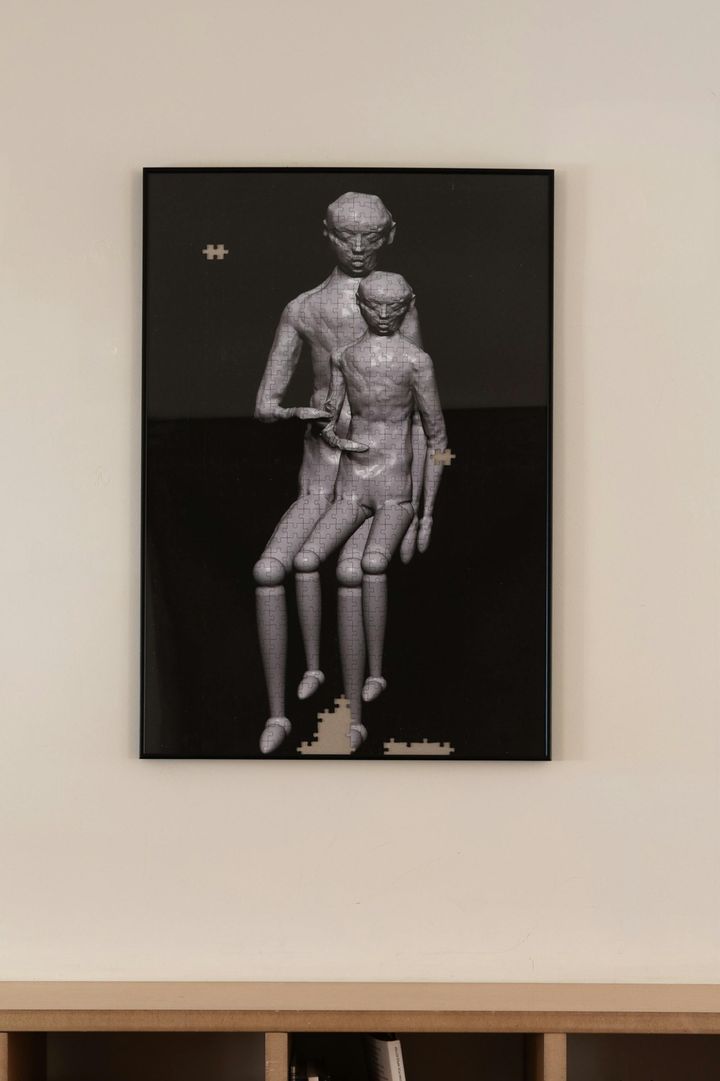

Object from the project In the Valley.

2021.

Puzzle. Edition 1/1+1AP.

75×52 сm (29,5×20,5 in)

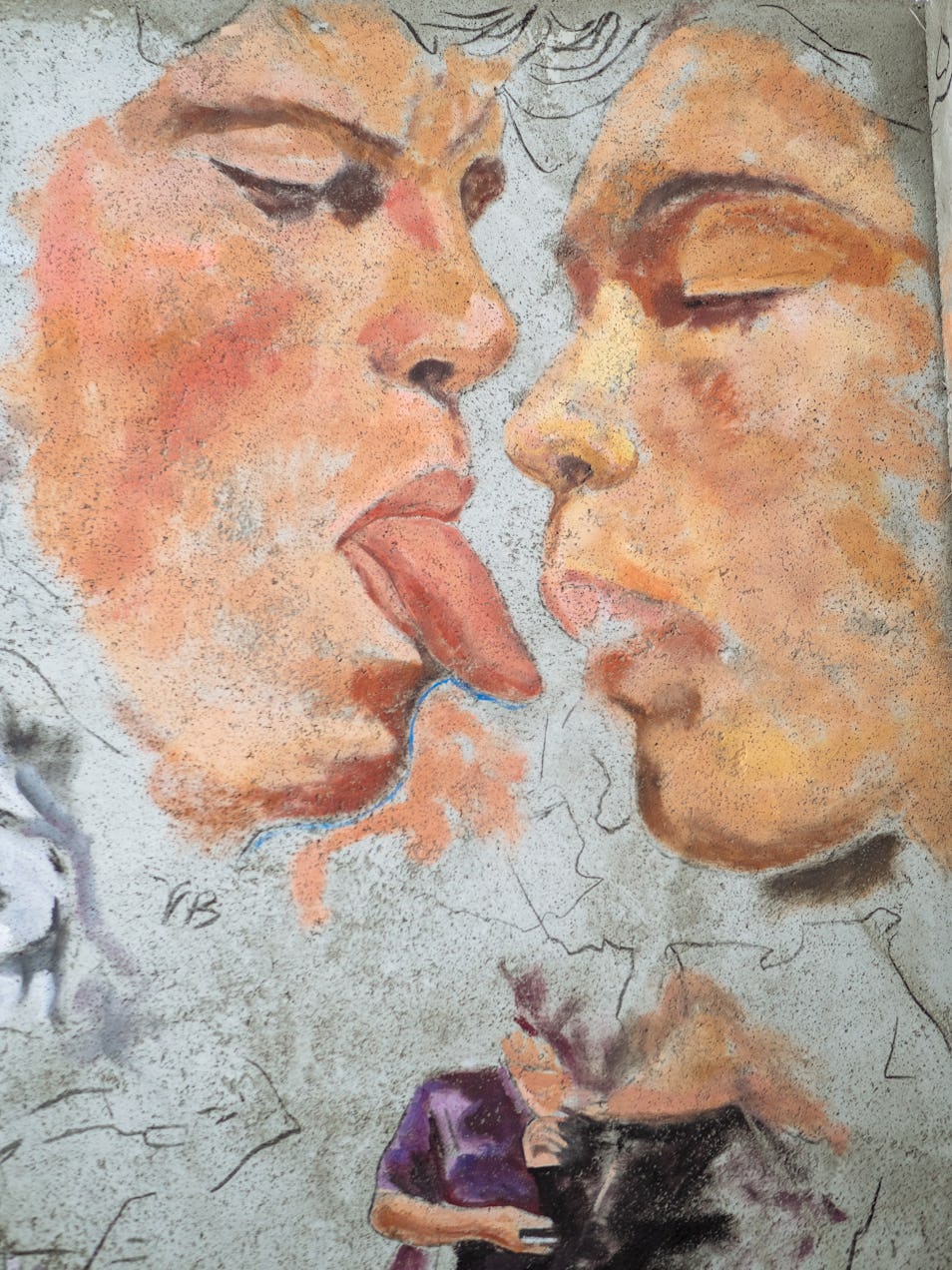

Object from the project In the Valley.

2021.

C-print, plastification. Edition 1/3+1 AP.

80×122 сm (31,5×48 in)

Object from the project In the Valley.

2021.

Plastic, 3-D printing. Edition 1/1 + AP.

16×40×17,5 сm (6×16×7 in)

Object from the project In the Valley.

2021.

Plastic, 3-D printing. Edition 1/1 + AP.

33×19,5×19,5 cm (13×7,5×5 in)

Object from the project In the Valley.

2021.

C-print, plastification. Edition 1/3+1 AP.

80×122 сm (31,5×48 in)

In the Valley

The glittering technological world in which we live increasingly resembles the disturbing spaces of contemporary shopping malls, pointing to the formidable machinery of capitalism built on the hedonism of consumption. The food we eat is industrially manufactured and genetically modified; our bodily processes are chemically enhanced; our homes are filled with devices that advise us and ask us to call them by name; every online action and manifestation of our personality is processed by software algorithms. The traditional differences between man and the technological sphere are dissolving, and considering the ways in which technology mimics the human. Such hybridization processes and their disturbing poetics are what Nikita Seleznev brings to light in his new project “In the Valley”. Ominous yet seductive, disturbing yet delicate, Seleznev’s works, created in collaboration with the architect Grigory Baluev, are fragments of anthropomorphic objects, surrogate bodies and abstract casts of disturbing reality, made of concrete and biodegradable plastic (3d printing), screens with 3d renders and graphic images. They question the rapidly disappearing boundaries between human and machine, animate and inanimate, and the deep psychology behind them, in particular the machinery of desire and control. The poetics of Seleznev's biomorphic objects recalls the hybrids of man and machine by Francis Picabia, in particular his 1914 painting “I See Again in Memory My Dear Udnie,” which was inspired by the sensual movements of a dancer. Like an abstract painting by Picabia, in which rhythm is transmitted through repeating interpenetrating pistons and holes that link the mechanical to the biological, the poetics of Seleznev's works demonstrates how technology mimics humans by appropriating human images and bionic forms. These objects seem to have fallen into a coma or are in hibernation, as if frozen in a cryo chamber but ready to wake up at the most unexpected moment.

The power of technologies to adapt to humans can be sensed in the algorithms that generate content recommendations on social networks, and in the study of youth slang, which engaged Seleznev in his past projects. These examples unfold the relationship between the human body, technological culture and the objects that surround it: technologies are not particularly intelligent, but they can affect the whole world, since they have a direct impact on billions of people. Aimed at maximizing the likelihood that the user clicks on the presented elements, the algorithms, it would seem, should offer the user what he knows he should like. But the strategy turns out to be different: the solution is to change the user's preferences, making them more predictable. A more predictable user can be offered items that he is more likely to click. In this way, profits increase and and people with more radical political views become more predictable choosers.

Like any rational entity, the algorithm learns how to change its environment (including user preferences) in order to maximize its own reward. Reacting to the adaptation of technologies to human emotions and behavioral models, Seleznev asks important questions about the transformation of our relationships not only with technical objects, but also with ourselves and our reality in an increasingly technologized world. By creating more machines and constantly updating them to replace our own labor, we humans will become inert. The alienating spaces of the global shopping mall, which have been engineered according to the psychology and psychosomatics of man, become yet another ruthless inhuman prosthesis that determines life experience and with frighteningly perfect architectonics. As these objects and spaces gain strength and take over our lives more and more, it is worth asking, ‘Who really controls our lives?” Challenging the false belief that we are able to control reality, Seleznev's works analyze how the elusive and changing nuances of technological development manifest themselves, how they adapt to the person, shape our perception, and condition our choices and experience of time and space.

The conceptual basis of Seleznev’s new project, the "Uncanny Valley" Effect is a hypothesis formulated by the Japanese robotics scientist and engineer Masahiro Mori. It implies that a robot or other object that approximates but does not replicate a human causes dislike and disgust in human observers. A human-like machine is no longer perceived as a technique. An anthropomorphic robot begins to seem like an unhealthy or inanimate person, revived by a corpse, causing the observer to fear death. In addition to the reminder of "memento mori", the overly symmetrical faces of androids cause cognitive dissonance with their implausibility, unusual for living people. Seleznev explores the eroticism of technological animism through hyperrealistic anthropomorphic images that are alienated from man and found in industrial and corporate design, often created according to a Frankenstein logic, as well as in consumer goods. He also pursues the spaces that Marc Augé called "non-places": architectures which adjust to a person and imitating his interests and emotional reactions. Spaces like shopping malls, food courts, airports and playgrounds pull one into a joyless feeling of obsessive hyper-consumption, likening life to visiting the attractions of a noisy amusement park, from which it is impossible to find an exit.

Written by Alexander Burenkov

Technology: Grigory Baluev

Photo documentation: Ivan Erofeev

Projects

- Unfinished project

- Shaving of the Christ

- Slowly Aging Children

- On the tip of the tongue

- In the Valley

- Suburbia

- Karate poetry

- My space 2.0

- My green crocodile

- Preparation of the transformer-bride

- Tell me, O Muse...

- Dasia's fairy tales

- Notes from the Morder

- Phonatory bands

- Pets

- My space

Q. What are the relationships and parallels between Russia at the beginning of the 20th century and now?

Q. How fantasy can be used to create alternative realities to escape propaganda and control.

Q. What is love?

Q. How have our relationships with others been transformed in a technologized world?

Q. How does one capture and experience existential soullessness of Russia high-rise suburbs?

Q. What is the character of the social network languages, particularly with the migration of images from scrins to reality and back?

Q. How can the anxiety of the modern world be expressed?

Q. How does one capture the estrangement of the inhabitants of Russia’s marginal districts?

Q. Why do humans have conflicted notions about privacy and openness, and a need and desire for individuality?

Q. How does the media use hatred and scandal for profit?

Q. What was the complex relationship between Fyodor Chaliapin’s and his daughter, Dasia?

Q. How does fantasy create images of desire?

Q. How does something out of the ordinary become habitual?

Q. How do we understand the complicated relationships between humans and their pets?

Q. What visual codes can be deployed create an artist's identity?