Unfinished project

2021

Installation. Video projection, LED architectural façade, screen.

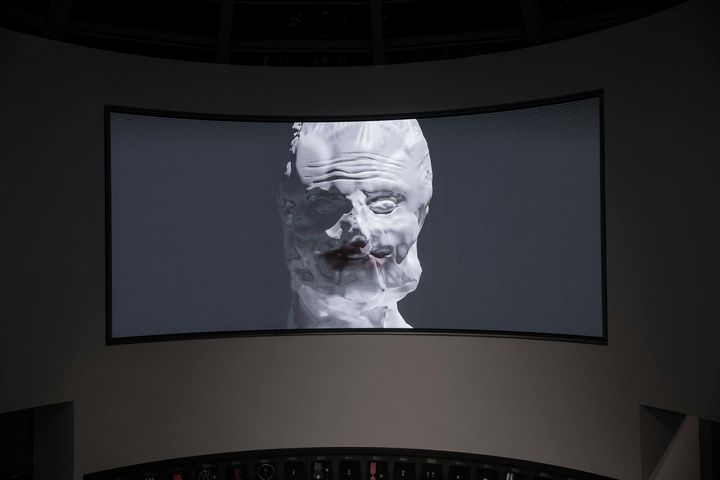

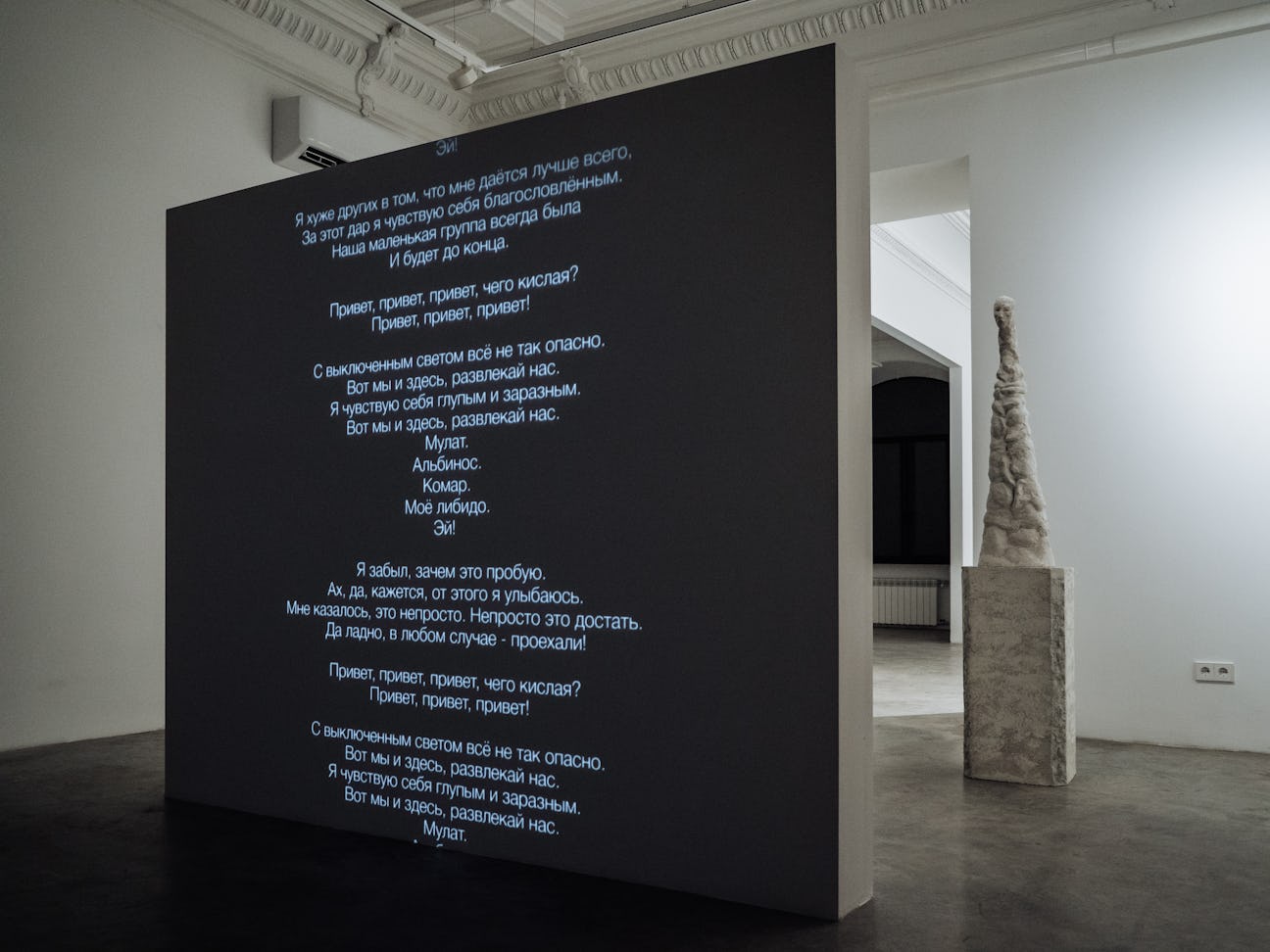

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

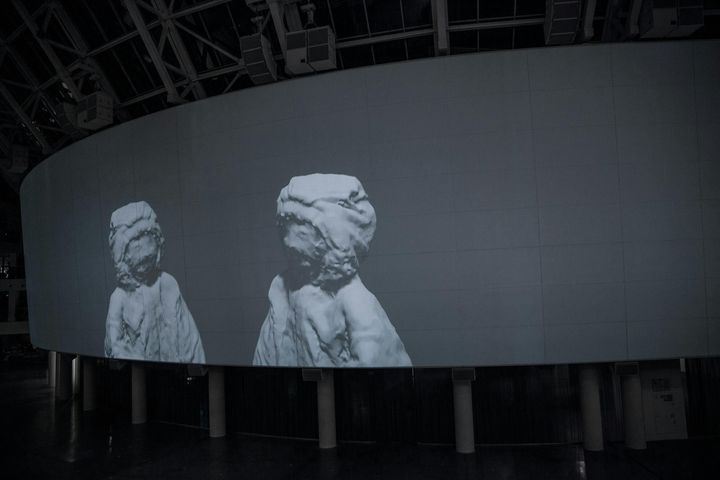

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

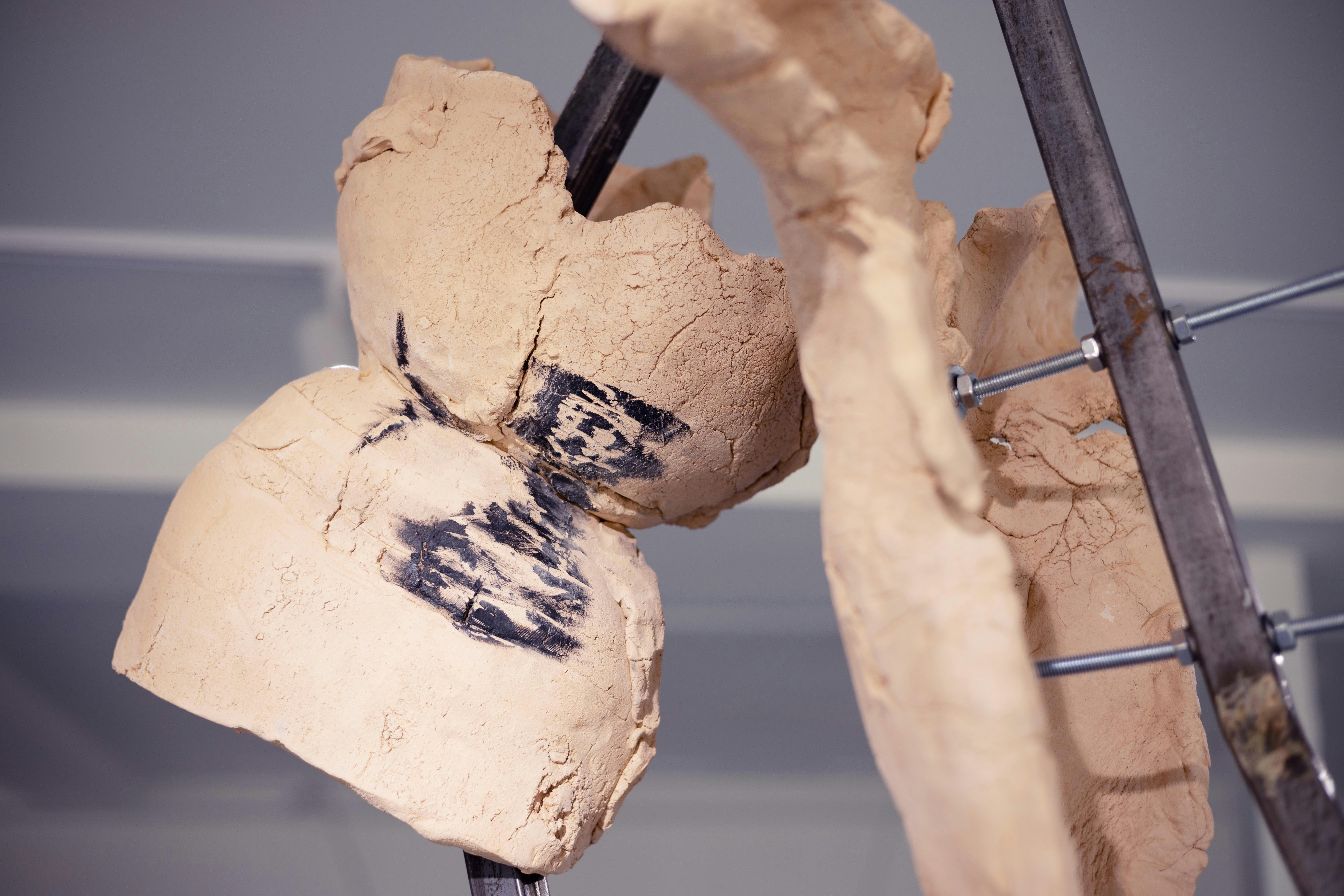

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

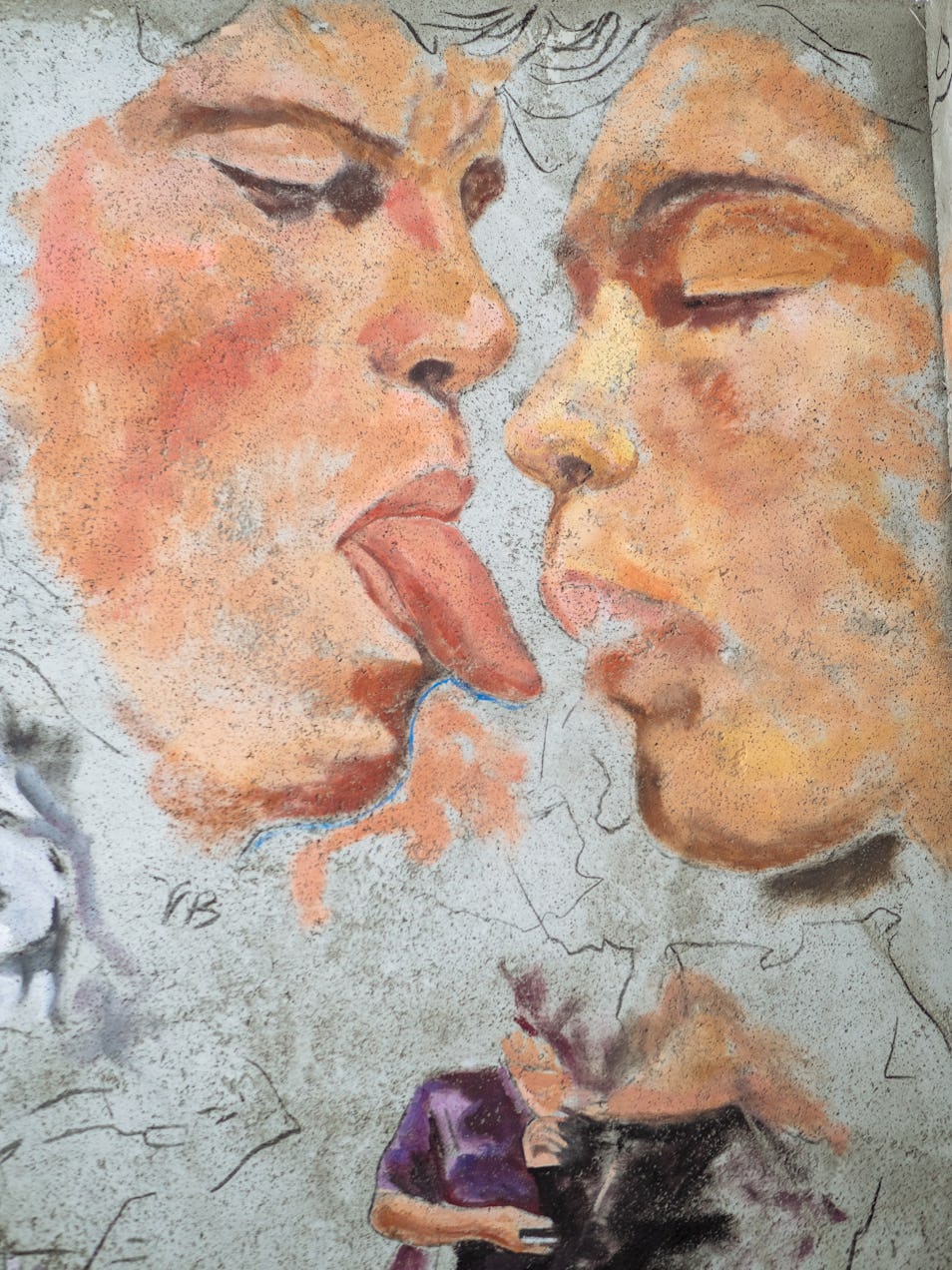

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

Installation view Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

Video documentation Unfinished Project.

2021.

The Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, Yekaterinburg

Sculpting with Time

Keine neue Welt ohne neue Sprache.

[There is no new world without a new language.][1]

Ingeborg Bachmann

When Nikita Seleznev temporarily installed Unfinished project at Ekaterinburg’s Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, the scale of the undertaking was staggering. Seleznev and his collaborators “unfolded” three works, as Oleg Lutohin put it, across the center’s largest screens, unifying them into a single work. [2],[3],[4] Each component was an often subtle, metaphorical reflection on the legacy of Boris Yeltsin’s failures and short comings and the dystopia that pervades contemporary Russia.

Seleznev was trained as a sculptor and a monumental sculptor at that. In Ekaterinburg, he has reapplied his training and skills in three dimensions, reusing them in video (or time-based media) works and projects. Through form and symbol, sight and sound and, above all, using time and timing, Seleznev offers subtle critiques of post-Soviet Russia.

To moviegoers, the pacing of Unfinished project is as languid as that of the late film-maker Andrey Tarkovsky, who defined his work as “sculpting in time.” [5] Tarkovsky explained:

Just as a sculptor takes a lump of marble, and, inwardly conscious of the features of his finished piece, removes everything that is not part of it—so the film-maker, from a 'lump of time' made up of an enormous, solid cluster of living facts, cuts off and discards whatever he does not need, leaving only what is to be an element of the finished film, what will prove to be integral to the cinematic image.[6]

Tarkovsky and Seleznev both animate their work using clusters of facts combined with elements of fiction, resulting in non-narrative experiences. Precise editing—that is, the assembly and reassembly of images and sequences—"disturbs the passage of time, interrupts it and simultaneously gives it something new. The distortion of time can be a means of giving it rhythmical expression.” [7]

The first, soundless projection in the center’s atrium is a continuous loop that stitches together animation of computer-modeled sculptures. The digital setting on screen looks like a great hall situated in a Brutalist structure. The work cycles through various tableaus much like a museum tour. First comes sculpture, borrowing from state-sanctioned art from the Soviet era, followed by skeletons, and then a couple sculpted in concrete, who seem to be modeled after one of Russia’s quickly disappearing, indigenous minorities. Next the great hall is gradually filled with an “army” of alienlike, genderless figures all of which are rendered in a style that might be best described as pre-sculptural. Finally, a disproportionately large, near-Cycladic manifestation, which looks like an idol of “mother and child” reigns over the great hall. Everything is stark, hard, cold, remote, and adrift.

A second, adjoining projection is closest to “pure sculpture,” conceived, created, and realized digitally. Two stationary figures rotate as if they are mounted on a sculptor’s turntable. It is impossible not to associate the figures, seemingly frozen in a pas de deux, with one of Antonio Canova’s neoclassical sculptures. The figures are “signature” Seleznev. They both look like they are made from plasticized frosting. As the couple rotates, the lips on the mouth of one figure morphs from happy face to kiss, from frown to pucker, before fading and nearly disappearing. The soundtrack combines synthesized rhythms and vocalizations which were collaboratively constructed. The results are eerie, drone-like interstellar static accompanied by murmurings from another world. There is a cold unreachable remoteness in the soundtrack.

The project’s third component is the easiest to explain. A heavily tattooed, genderless human form floats in a starless space. The body’s ink—its tats—range from banal to tribal, from gangster to ritualist. Its levitation is accompanied by an appropriately anemic soundtrack, like a prelude to a funeral service in a village church. Think of how Tarkovsky used levitations and music in Solaris (1972), The Mirror (1975), and The Sacrifice (or Offret) (1986). (Tarkovsky’s levitations are never cheerful ones.) Seleznev and his collaborators expertly leverage Tarkovsky’s sensibilities but remain detached from directly quoting his visual references.

Each component expands Unfinished project exponentially. Time is nonlinear, yet as a medium it has a distinct shape sculpted by Seleznev, which encapsulates a limbo-like space, a space of nothingness. Like Tarkovsky, Seleznev slowly builds tension in his immersive cinematic projections. His collaborators’ sound design underscores that tension, which never culminates in any kind of release. Writing about the films of Roman Signer, the Swiss sculptor, Brian Butler suggested that Signer’s films were made “to be ‘experienced’ as projections in space. We, the viewer, desire ‘authentic’ experience, but we will never get it.” [8]

Tarkovsky’s films have been referred to as “unabashedly poetic.”[9] The same is true of the 2- and 3-D works that Seleznev has exhibited in the last two years. Like Tarkovsky, Seleznev’s projects have evolved to “become one work. . . . [where] the mood is sustained” and can be modified, amended and, even, completed in the future.Tarkovsky’s philosophy was to present life “[10] as it is, . . . not through cinéma vérité, but through metaphors and a poetic stylisation, to more accurately depict the way each of us experience life.” Seleznev shares this approach, but his visual poetry is more suggestive than declarative and, in sculptural terms, coarser right down to his surface finishes.[11] Unfinished project is a sort of a “controlled experiment with no hypothesis.”[12]

[1]Ingeborg Bachmann. Darkness Spoken: The Collected Poems. (P. Filkins, Trans.) (Brookline, MA: Zephyr Press, 2006): xxxi.

[2]Grigory Baluev (technology), Alexandra Generalova (text), Marina Karpova (sound), and Oleg Kamenskikh (video documentation.

[3]Director of the Boris Yeltsin, Museum at the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center.

[4]Oleg Lutohin, email message to author, June 10, 2021.

[5]Andrey Tarkovsky. “Sculpting In Time: Reflections On the Cinema”. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987.)

[6]Andrey Tarkovsky. “Sculpting In Time: Reflections On the Cinema”. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987): 63-64.

[7]Andrey Tarkovsky. Sculpting In Time: Reflections On the Cinema. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987): 121.

[8]Brian D. Butler. Roman Signer: Sculpting in Time. (Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag, 2009): 10.

[9]Tulika Bahadu. “On Art and Aesthetics,” accessed June 22, 2021.

https://onartandaesthetics.com/2016/12/04/sculpting-in-time/ accessed June 22, 2021.

[10]Gavin Keeney. Knowledge, Spirit, Law., Book 1. (Brooklyn: punctum books, 2015-2017): 11

[11]Gavin Keeney. Knowledge, Spirit, Law., Book 1. (Brooklyn: punctum books, 2015-2017): 11

[12]I have borrowed this phrase from Brian Butler. Brian D. Butler. Roman Signer: Sculpting in Time. (Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag, 2009): 13.

Written by Clayton Press

Technology: Grigory Baluev

Sound: Marina Karpova

Photo and video documentation: Oleg Kamenskikh

Projects

- Unfinished project

- Shaving of the Christ

- Slowly Aging Children

- On the tip of the tongue

- In the Valley

- Suburbia

- Karate poetry

- My space 2.0

- My green crocodile

- Preparation of the transformer-bride

- Tell me, O Muse...

- Dasia's fairy tales

- Notes from the Morder

- Phonatory bands

- Pets

- My space

Q. What are the relationships and parallels between Russia at the beginning of the 20th century and now?

Q. How fantasy can be used to create alternative realities to escape propaganda and control.

Q. What is love?

Q. How have our relationships with others been transformed in a technologized world?

Q. How does one capture and experience existential soullessness of Russia high-rise suburbs?

Q. What is the character of the social network languages, particularly with the migration of images from scrins to reality and back?

Q. How can the anxiety of the modern world be expressed?

Q. How does one capture the estrangement of the inhabitants of Russia’s marginal districts?

Q. Why do humans have conflicted notions about privacy and openness, and a need and desire for individuality?

Q. How does the media use hatred and scandal for profit?

Q. What was the complex relationship between Fyodor Chaliapin’s and his daughter, Dasia?

Q. How does fantasy create images of desire?

Q. How does something out of the ordinary become habitual?

Q. How do we understand the complicated relationships between humans and their pets?

Q. What visual codes can be deployed create an artist's identity?