On the tip of the tongue

2021

Installation. Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

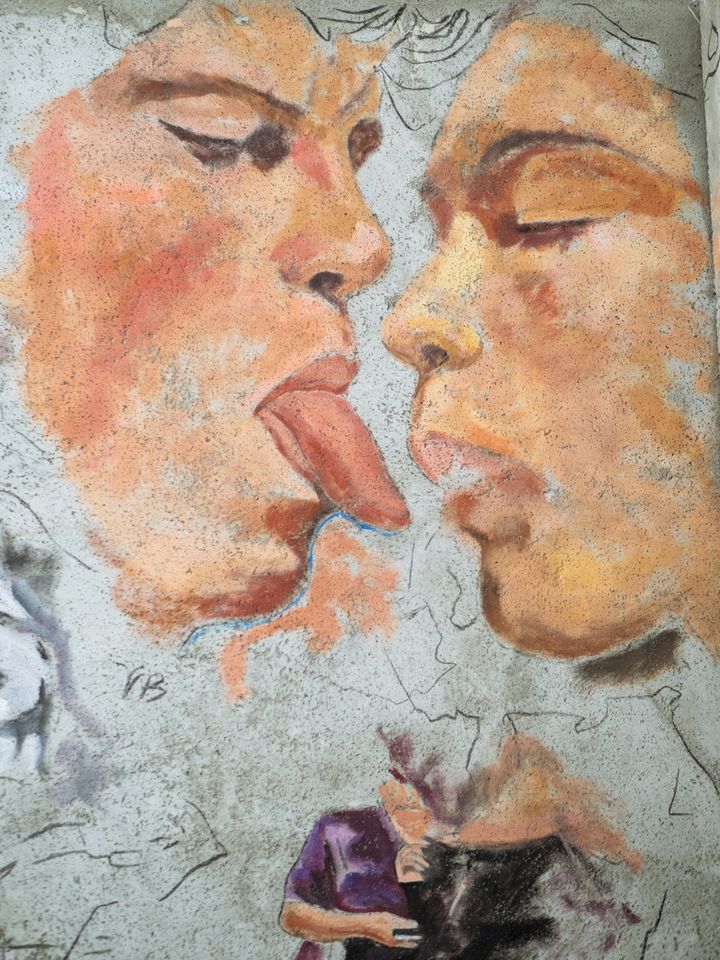

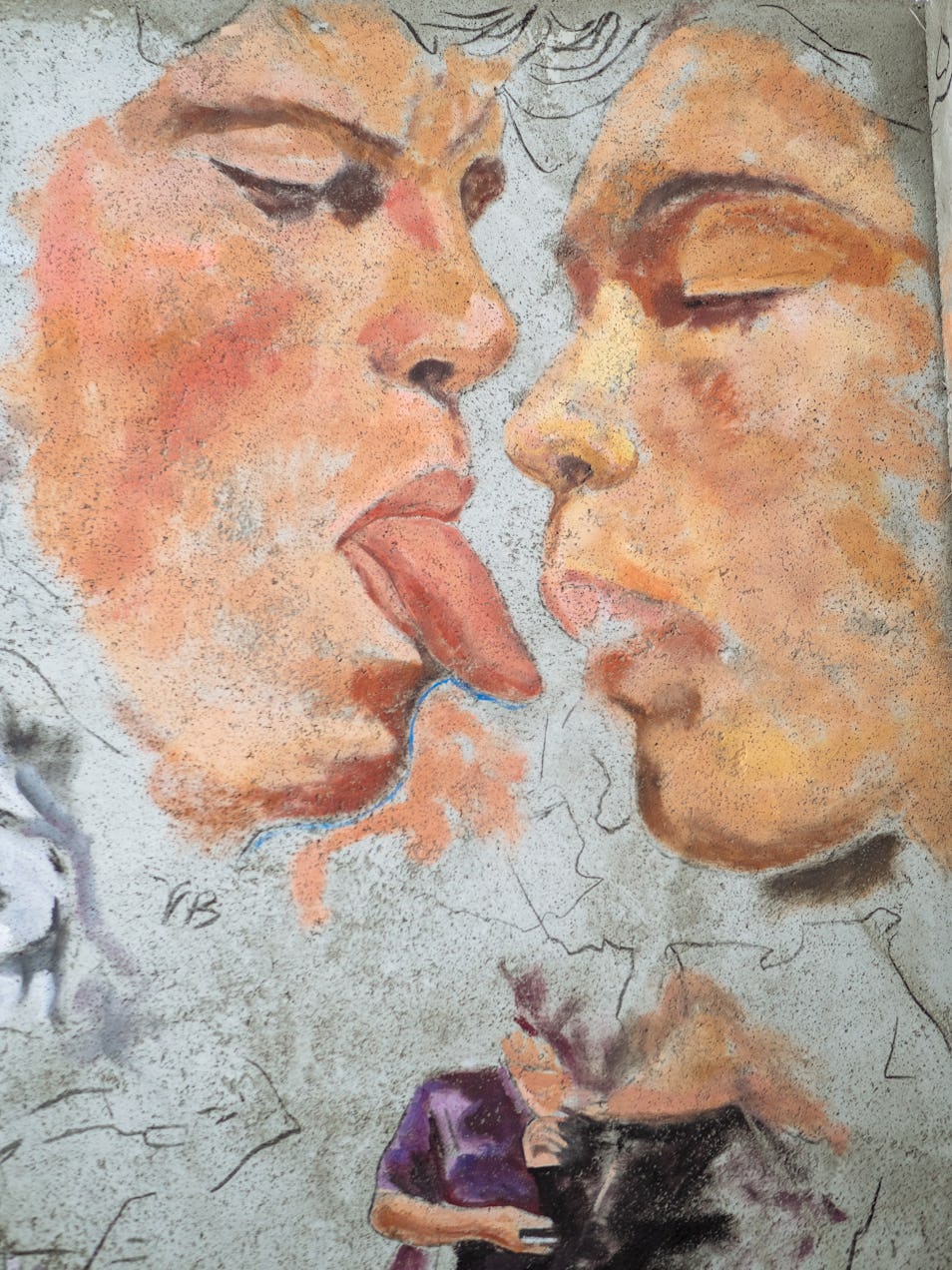

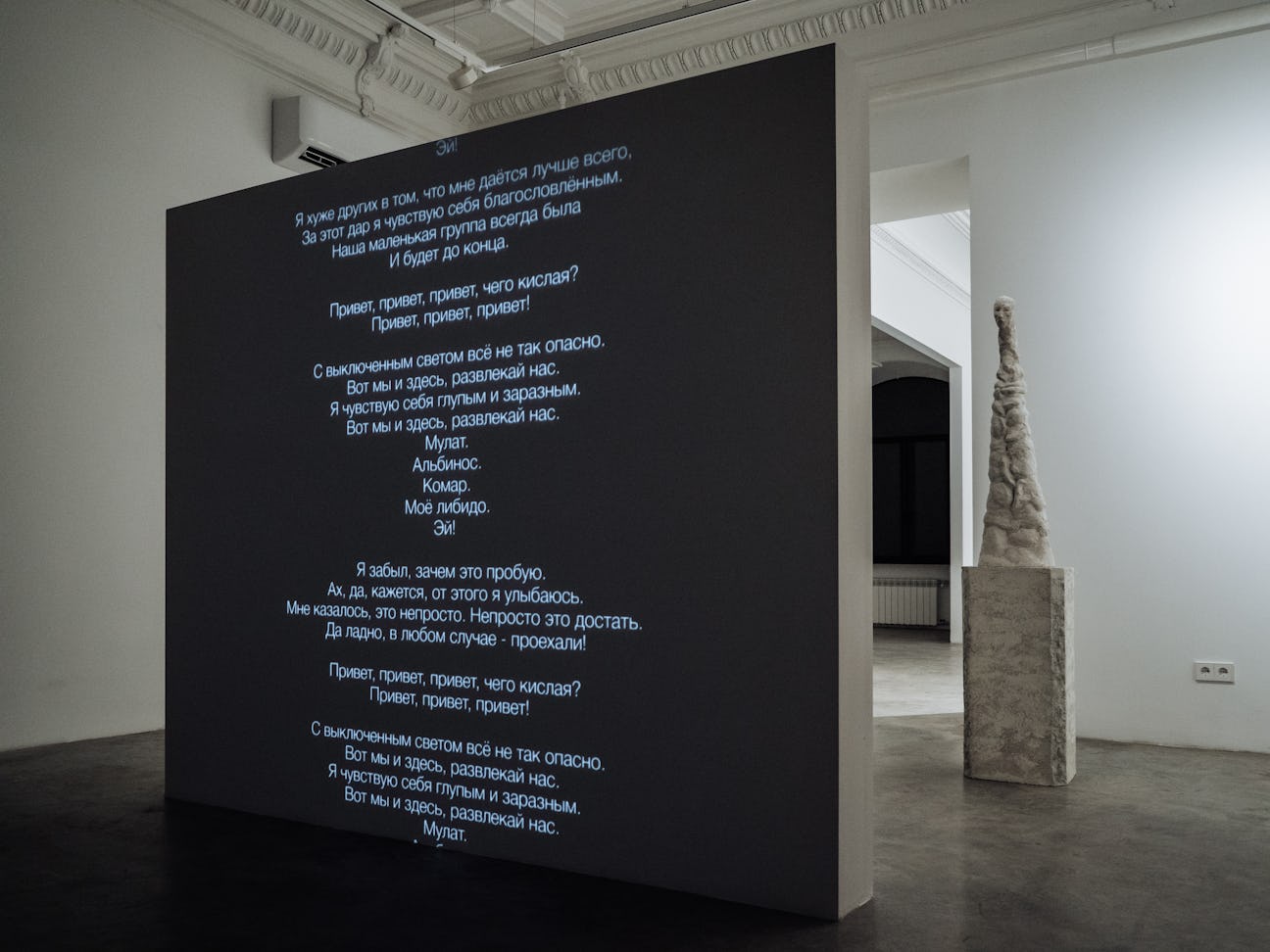

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

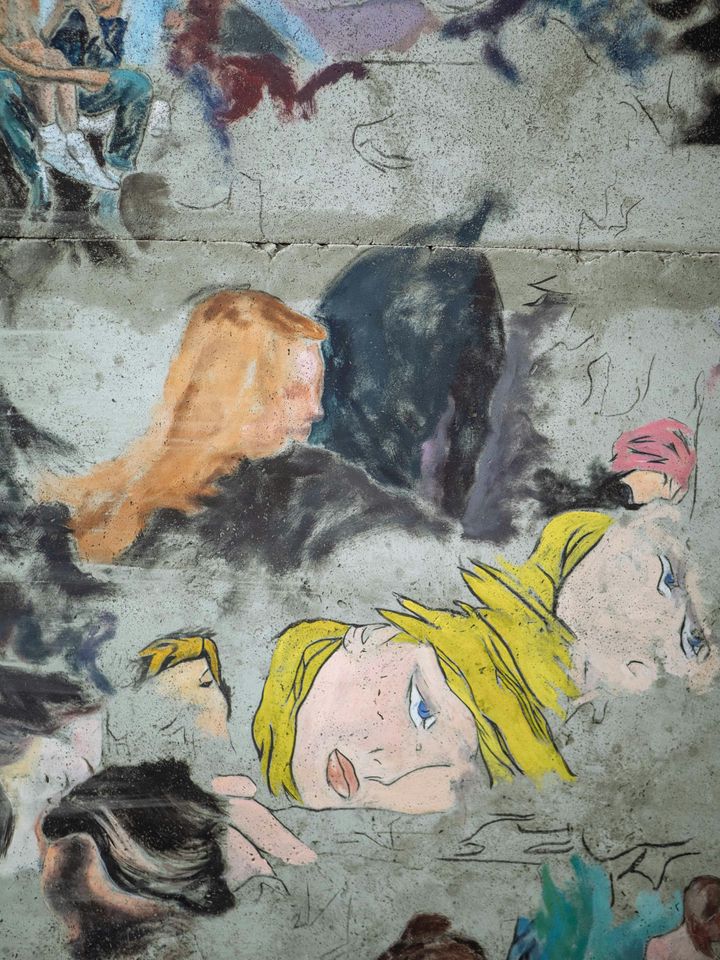

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

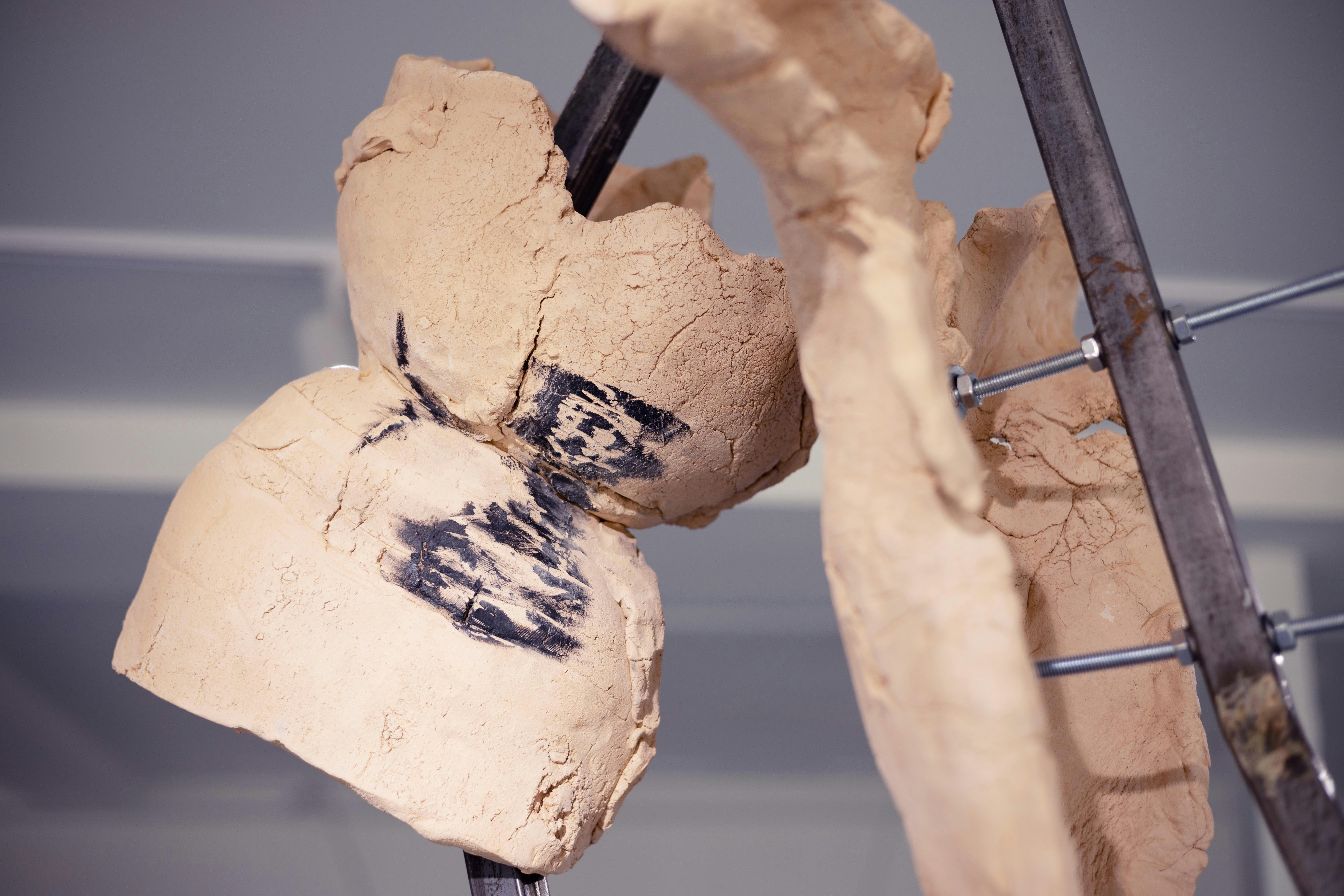

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

Installation On the Tip of the Tongue. Fragment.

2021.

Architectural concrete, acrylic painting, found object, screen.

232×228×4 cm (91×89,5×1,5 in)

On the tip of the tongue

In the amorous realm, the most painful wounds are inflicted more often by what one sees than by what one knows. [1]

Here begins the story of a love affair... and here it ends. Not because I do not wish to share my feelings—in fact, I am trying very hard to. I am focusing all my emotional energy on the event of love in order to displace this damn narrative. “Any minute now,” I think, “I’ll crack the riddle: I’ll find the ultimate words and gestures to fully express (give voice to) myself, without a trace of ambiguity, without incoherent mumbling and stumbling from subject to subject and event to event.” But it is in vain. My story won’t come together, and its figures suddenly start “occur[ing]... without any order, for on each occasion they depend on an accident... The figures are... non-narrative... they stir, collide, subside, return, vanish.” [2]

I live many lives at once: I act headlong, I go overboard, I feel pity for myself and desire for the other, I give suggestive and melodramatic excuses, I make do with hints, I keep silent, I get angry... The thought that these events do not exist in reality is torturous to me, and I flee to fictional worlds, preferring to simply ignore that the lover’s discourse is an imaginary discourse. [3] Edward Limonov describes this in his novel It’s Me, Eddie, one of the best-ever works on love: “My friends, if you ask why I didn’t find myself another woman, the truth is, Elena was too splendid, and anything else would have seemed squalid to me in comparison with her little peepka. I’d rather fuck a fantasy than a vulgar woman.” [4]

Falling in love is Elenas’ imaginary cunts. I rush restlessly from one to another—until I suddenly notice a crack in the containment shell of my love experience. It’s as if I then crawl out of this impassably dense thicket onto a worn, familiar trail by borrowing ready-made excerpts from love’s script from visual culture. I am relieved that the myriad images at my disposal allow me to demonstrate my being in love. They turn any emotional breakdown into its visual equivalent, and my feeling becomes “something that has been read, heard, felt” (or what I imagine I have read, heard, felt). [5] Captivated by this discovery, I let slip the moment when I still loved the way I love to, not the way some grammar dictates.

These reflections were inspired by Nikita Seleznev’s work On the Tip of the Tongue (2020). One distinctive feature of this video, available online, is often attributed to digital art: digital media allows the artist to combine different forms of art, leading to a blurring of the differences between different types of materials. The reality of the thing “in front of us’ is constantly being called into question. [6] The video’s visuals are collaged from social media photos of kissing couples, embraces, and erotic scenes, as well as from movie footage and details of artworks on the subject of love. Seleznev has translated them into paintings on concrete slabs, forming a spatial composition augmented by two sculptural elements of varying natures—real and virtual. He underscores the two-fold nature of the materiality of the objects represented in the video, thus calling into question the reality of the experiences and feelings to which the images point.

Out of these details, particulars, and excerpts of love scenes, Seleznev systematizes a modern conception of love. He arranges this feeling, so complex to represent, into a visual canon with its own set of plots, compositional guidelines, and stage blocking. We are aware that we are in love and declare our love by checking it against the clichés of lovers’ behavior and repeating them as best we can: just one more joint selfie holding hands... The event of love does not fit into the immediate order of things, [7] and we feel the need to get the better of this ambiguity, this unknown, this opaqueness resonating inside us. Wishing to admit that we are in love, that is, defenseless, we simultaneously search for and find emotional support in the virtual realm, immersing ourselves in its visual excess. But this is a mistake. It is not performing the lover’s discourse; it is falling into its trap.

The images of love Seleznev places in a hypermedia context destroy the illusion that love has a solid ontological basis, and even turn it into a cliché. I haven’t cracked my riddle. I can speak about my love, concisely or verbosely, but its essence remains where it was—on the tip of my tongue.

[1] Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, trans. Robert Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), 132.

[2] Ibid., 6–7.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Edward Limonov, It’s Me, Eddie: A Fictional Memoir, trans. S. L. Campbell (New York: Random House, 1983).

[5] Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, 4.

[6] Christiane Paul, Digital Art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2015).

[7] Alain Badiou, “What is Love?,” trans. Justin Clemens, Umbr(a) no. 1 (1996): 37 53.

Written by Alexey Maslyaev

Translated by Elias Seidel

Projects

- Unfinished project

- Shaving of the Christ

- Slowly Aging Children

- On the tip of the tongue

- In the Valley

- Suburbia

- Karate poetry

- My space 2.0

- My green crocodile

- Preparation of the transformer-bride

- Tell me, O Muse...

- Dasia's fairy tales

- Notes from the Morder

- Phonatory bands

- Pets

- My space

Q. What are the relationships and parallels between Russia at the beginning of the 20th century and now?

Q. How fantasy can be used to create alternative realities to escape propaganda and control.

Q. What is love?

Q. How have our relationships with others been transformed in a technologized world?

Q. How does one capture and experience existential soullessness of Russia high-rise suburbs?

Q. What is the character of the social network languages, particularly with the migration of images from scrins to reality and back?

Q. How can the anxiety of the modern world be expressed?

Q. How does one capture the estrangement of the inhabitants of Russia’s marginal districts?

Q. Why do humans have conflicted notions about privacy and openness, and a need and desire for individuality?

Q. How does the media use hatred and scandal for profit?

Q. What was the complex relationship between Fyodor Chaliapin’s and his daughter, Dasia?

Q. How does fantasy create images of desire?

Q. How does something out of the ordinary become habitual?

Q. How do we understand the complicated relationships between humans and their pets?

Q. What visual codes can be deployed create an artist's identity?